a comedy, a tragedy, and the home of Ernest Hemingway.

On my existential crises, a guardian angel, and my visit to the home of Ernest Hemingway

If it was 2022 and the month of September, and it was the day after my birthday, I would be in Key West, Florida. If it was the following day, I’d still be in Key West, Florida, but I’d also be in the back of a police car with what was most likely a cracked rib. Maybe it was a fracture, but without health insurance, I had no way of finding out.And if it were later on in the day, my ankle and wrist would be wrapped in bright painter's tape blue bandage, and I would be walking—or limping—to Ernest Hemingway’s house.

Thankfully, without health insurance, I didn’t have to bother with going to a hospital and could dedicate the rest of the day to the home of my literary hero.

The day after my birthday in 2022 was September 23rd; that means my birthday is September 22nd, which is also Bilbo and Frodo Baggins’ birthdays if you care. My friends and I were flying to Miami from Hartsfield-Jackson, where we would then rent a car and drive the four-or-so hours of bridges and island roads to Key West, the southernmost tip of the United States of America. If you’re wondering why I didn’t fly straight there, it’s because I didn’t make enough money to have health insurance, much less a direct flight to Key West.

Anyway, it was September 23rd and the drive down was beautiful. Not a hurricane in sight (yet), just blue skies and bluer seas; back then, it was called the Gulf of Mexico. The first day and a half were spent pleasantly with seafood and snorkeling and sightseeing. But on the following day, I would get to see Ernest Hemingway’s house. If you know me well or at all, you probably know that I have a strong fascination with him. And not just his writing, but his life and general aesthetic. The fishing and adventure and Paris and Cuba. There was a largeness to the way he lived life, and although it was cut short and ended very darkly, I still find the abundance of it intoxicating. And, in truth, I’ve been a bit conditioned to feel this way.

Growing up, my grandparents owned and still own a beachside condo in Florida; the master bedroom was Hemingway-themed. There was an old typewriter next to the window and a stack of his books and biographies and a portrait of him on the wall. So, from a young age, being interested in literature, I became attached to the mysticism of him. He truly was the Old Man by the Sea. I felt drawn to the salty air, the Gulf, the idea of being a writer, to the romanticization of Paris (I would later minor in French; I cannot speak French). I have seldom written a word in the English language without thinking of his art of brevity. He would probably tell me I’ve written too much already, but I’m not trying to be great, only funny and hopefully a bit profound.

His house in Key West was something of a Mecca for me; it was much easier to get to than the one in Cuba, anyway.

Did any of my friends care about this at all? Of course not. But they would humor me nonetheless.

We were there to have a fun girls' weekend; I was there, too, to see his house and hope that perhaps some of his genius would be absorbed in me. At the very least, I would have a souvenir from the gift shop and bragging rights.

The morning of our second full day, we decided to rent mopeds; I had never before driven a moped, but I’d grown up around four-wheelers and the likes, so how different could it be? One of us paid and signed the papers and we all swore we had experience and did not need to be taught.

You know in the Bible when they say, “Pride goeth before the fall”? That was made manifest in me that day.

I was nervous about driving the moped. It wasn’t like the little Vespas you see in Roman Holiday or that Lizzie Maguire movie in Italy. It looked more like a motorcycle; large, bulky, heavy.

But I’d be damned before admitting this to my friends; for if I could not drive a moped, who was I? What were those years growing up on land for? If any of us should be able to do this, it should be me. I now apologize to my friends for this thinking; it was truly reflective of myself rather than them.

For it was I who got on it despite my reservations, and it was I who drove it and myself and my friend into the back of a parked car while turning left at an intersection.

My first concern was of spinal fracture (if you know me, you know why). My second concern was that I’d maimed my friend. My third concern, though I’m not certain, was probably what everyone would think of me. When it was apparent neither of us were seriously injured—thank the Lord—my next focus was on addressing the sudden appearance of a local policeman. I watched him collect my lone Birkenstock from the middle of the street and bring it to me. He asked how we were, and he asked if we needed to go to the hospital; it went something like this:

“Are you okay?”

“I think so.”

“What hurts?”

“My wrist and my ankle, but it’s not too bad.” Desperate nodding.

“I think you should go to urgent care, just to be safe.”

“No, please sir, we don’t have health insurance. I think we’ll be fine.” Desperate head-shaking.

My friend, in tears: “Is she going to have to pay for this?”

Pathetic.

“Can I see your license?”

It was in the other moped.

We called our two friends, who neatly drove their still-operational moped to us and I retrieved my license.

And here, my friend, is the only time in my life I’ve questioned the theological likelihood of a guardian angel; and if he was not that, perhaps he was a regular angel and I know those are in the Bible in disguise all over the place.

Tyler the cop was so kind. He did not arrest me for crashing a moped into a parked car without a license on my person. He did not write me a ticket. He even gave us a ride to our parked car. The car seats in the back of a police cruiser are made of hard plastic, by the way, and are divided by plexiglass. Tyler was compassionate and caring and not condescending. In truth, the whole thing seemed kind of funny just then. We were able to laugh about it and recognize the situation as a great future anecdote or story to tell at a party. Or, perhaps, write about on Substack.

But in that moment, being able to recognize unnecessary kindness in another person and attribute that to a transcendental Christian virtue was a sweet thing. Is it a testament to man’s sin that to find unexpected kindness in another seems angelic, or is it a testament to man’s ability to transcend sin and become like an angel—good, true, righteous, considerate? I don’t know.

I later googled him and found out he’s not an angel. However, his wife’s Facebook posts make him seem like the generous and nice man he was to us. If you ever read this, Tyler, thank you for being a good person!

Once we were all patched up with CVS brand bright blue bandages, we were ready to take on the town again; and I was ready to visit The Hemingway Home and Museum.

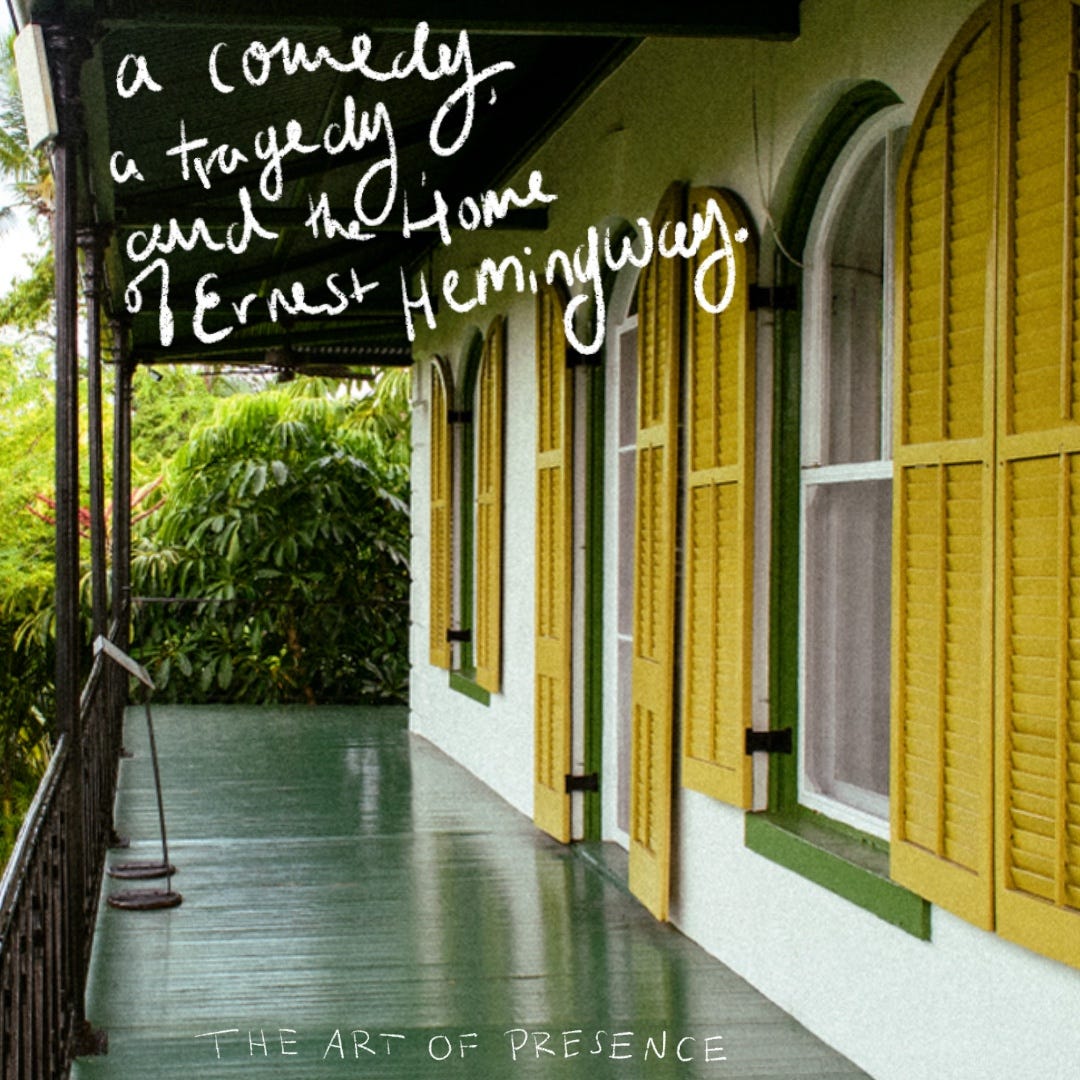

It was a hot September day, and the house was situated in a jungle oasis in the middle of the bustling island. Tall palm trees and leafy plants and winding paths were a mote between the house and the street. Dotted lazily among it all, both inside and out, were six-toed cats. The anomaly felt a bit random, but then so had the whole day so far, so it seemed right.

His writing room was filled with bookshelves and comfortable furniture and taxidermy and French doors. There was an essence of real life in getting a peak into the atmosphere of a great writer; it’s something I think is lost in the attempt of this through social media and modern-day writers.

The home was beautiful and old and eccentric and well lived in. There was luxury in the pool, humility in the small tiled bathrooms, and otherworldliness in the memorabilia and artifacts and polydactyl cats. It was evidence that Hemingway was both the myth and just the man, somehow at the same time. He had a gift and a career I would only dream of having; and yet, his life ended in emptiness and tragedy. Perhaps there’s a lesson there on discontentment or looking for abundance in the wrong places, but the truth is that sometimes life is hard and people do things we can’t and won’t understand, and dark mysteries remain in the shadows.

The gift shop, naturally, was filled with his books and t-shirts, and other paraphernalia. And no matter how strange this modern world is about the commodification of a life—I still bought a souvenir. What can I say? I needed the special edition of the Old Man and the Sea.

That evening, having seen what I came to see and survived the violence of a moped accident, I felt satisfied. My friends and I were walking to dinner I think, or just roaming around, where I received a call.

$900. That’s how much a moped accident costs you when you don’t sign the $10 insurance policy they offer.

If I have not foreshadowed this enough, I was not in a great place in my career. I had savings, sure, but I was in the middle of what would become a failed attempt at entrepreneurship. I was desperately trying to get a small business off the ground, but my income had remained, for a long time, inconsistent and unstable. I felt lost in my life; God didn’t seem to be answering any of my prayers and things that I thought would work out, doors I thought would open, remained firmly shut; or not there at all. Perhaps there had been a build-up until this point; perhaps the passing of my 25th birthday added to it; and perhaps that $900 was enough to tip me over the edge.

I paid the bill and sat, alone, at the marina staring at my reflection, despairing of life itself.

It wasn’t about the money. It was that, somehow, the event and the failure to recognize my own inability to drive a moped (I am being very serious, please do not laugh) represented my perceived failure in real life. And that vibe is a real harsh bummer to carry on vacation; just ask my friends.

The vacation ended with a hurricane-drenched drive back to Miami, running through the airport on a couple of sprained ankles, and an even pricier bill from the other car’s insurance company (another story for another day).

But as I reflect on that weekend now, I find it to be a formative part of my life. Representative, sure, of a dark time that lasted longer than I’d care to admit; but also full of inspiration and life and goodness.

Later that year, I would go on to—in the unfortunate free time and flexibility of a fledging business—write my first serious piece of writing: an Advent series called Giver of Gifts. This would be the first time I began to share my writing with people.

The following summer, I wrote an essay on the dark time that began on this trip. That essay would end up being my first published piece of writing. It was also the season in which my business finally failed, and I moved to Nashville, Tennessee following a prayer and the job I have now. Here in Nashville, I was able to read said essay at an event, also a first. And at that event, another kind person paid me a compliment on my writing and referenced, yes, Hemingway.

Life has a funny way of turning out.

But I think this taught me two things:

First, bad times are real and long and hard. God cultivates good out of the bad parts of our lives, yes, but we often don’t see that until much later, if at all.

Second, good things can happen amid hard times. God can bring about a glimmer of hope even in a rotten situation; or maybe send an angel; or maybe send a very nice man.

For the past few years, I’ve told my friends we need to go back to Key West and redeem it. But now, as I write this, I wonder if it has been redeemed in its own way.

I’ll still go back though, and I will never get on a moped for as long as I live.